The world of human resources keeps getting more interesting, especially as it relates to employee medical issues. From aging baby boomers with physical limitations to workplace injuries, employees with health conditions, and now the legalization of marijuana in some states, the line between what’s permissible and what’s restricted in the workplace is blurred. On top of all this, the definition of a “disability” in employment has greatly expanded. It all points to one thing: Employee medical issues will increasingly plague employers.

Managing employee medical issues in the workplace has gotten more complex and challenging due, in large part, to several employment regulations that come into play, including workers’ compensation, the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) and the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). To minimize risk, it’s best for employers to proactively address employee medical issues rather than wait until it’s too late, especially when the ADA is involved, says Jean Seawright, president of Seawright & Associates, a human resource consulting firm based in the Orlando area. Otherwise, you could quickly and unexpectedly find yourself on the defense.

ADA Overview.

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) was passed into law in 1990 and is a “comprehensive federal civil rights law that prohibits discrimination on the basis of disability,” similar to protecting the rights of individuals on the basis of race, sex, national origin, age and religion. This legislation ensures equal opportunity for individuals with disabilities in employment, public accommodations, transportation, state and local government services, and telecommunications. This well-intended law has caused a firestorm of controversy over the definition of “disability” with regard to employment regulations.

In 2008, to help resolve confusion and provide clarification of the ADA, the Americans with Disabilities Amendments Act (ADAAA) was passed. These two acts are often collectively referenced as the “ADA.”

“While the intent of the ADAAA may have been clarification, there’s an unfortunate little sentence in the implementing regulations that has made compliance more challenging for employers,” Seawright said at NPMA’s 2013 PestWorld convention and tradeshow. This sentence refers to the definition of a “disability” and essentially makes it easier for an individual to claim that he or she has a disability.

Based on the implementing regulations and the government’s intention to construe the definition of disability “broadly in favor of expansive coverage, to the maximum extent permitted by the terms of the ADA,” Seawright advises employers not to get hung up on trying to determine whether or not a medical condition meets the definition of a disability. In many cases, “it’s better to treat it like it is a disability,” advised Seawright. As a result of this new enforcement philosophy, millions more people have found coverage under the Act.

|

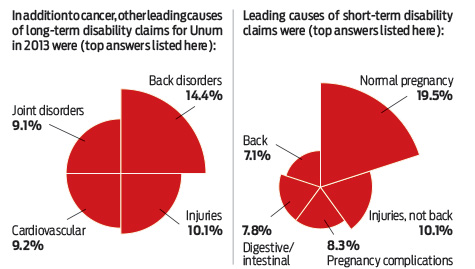

Cancer is Leading Reason for Long-Term Absence from Work Cancer is the leading reason employees stop working and take long-term disability leave, according to claims submitted to Unum, a leading provider of disability insurance. Unum analyzes claims activity each year and shares results during Disability Insurance Awareness Month (May) to help foster a better understanding of the value of disability insurance and other coverage. Highlights from this review of 2013 data shows:

“Recovery and return to work play a particularly significant role for cancer patients,” says Robert Jacob of Unum. “Early detection and treatment options have improved dramatically, so the focus for cancer patients is on living beyond the disease. A rewarding career, network of coworkers and support of the employer are key motivators for recovery.” |

The U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) is responsible for enforcing ADA and has the authority to investigate charges of discrimination filed by applicants, employees and ex-employees against employers. The EEOC’s role is to investigate the allegations in a charge and determine if illegal discrimination has occurred. A mediation option is available in many cases. When a charge is not resolved through mediation and the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission determines that illegal discrimination occurred, if the parties cannot reach an agreement on the remedy, EEOC or the claimant can file a lawsuit against the employer.

Likely at Risk.

Most employers with 15 or more employees are covered by ADA, as are most labor unions and employment agencies. Employers with fewer than 15 employees, although they may not be covered by ADA, may be covered under a similar state regulation that applies to smaller businesses. Both state and federal anti-discrimination regulations apply to all terms and conditions of employment including: hiring, firing, promotions, training, wages and benefits. In other words, if your business is covered under the ADA or another anti-discrimination law, you must ensure that virtually every employment decision you make is non-discriminatory. And you must be able to prove it.

“When filing a charge of discrimination, employees don’t need to provide proof or evidence of discrimination,” said Seawright. “It’s simple. All they need to do is file a complaint that they were discriminated against. They can say whatever they like, true or not.”

Why?

The EEOC operates under the principle that the burden of proof is on the employer. “The burden rests solely on the employer,” explained Seawright. “When someone alleges discrimination, the employer is the one who has to prove there was no discrimination.”

In 2012, the latest year with reported statistics, the EEOC received more than 99,000 discrimination charges and recovered more than $365 million on behalf of those alleging discrimination. There’s no doubt the potential financial damage to a company defending a discrimination claim can be devastating. The most prevalent charges of discrimination, in order, were race, sex and disability. The top five disabilities are not what one might consider to be traditional disabilities: back impairments; non-paralytic orthopedic impairments; limb-related disabilities; depression and anxiety disorders; and cancer.

To help ensure compliance and minimize ADA risk, it’s critical for employers to clearly understand several key terms in the regulation. For example, what exactly is a “disability”? And, what is meant by providing a “reasonable accommodation” to someone with a disability? Since a reasonable accommodation must be provided to a qualified individual with a disability unless it creates an undue hardship on the business, what then constitutes an “undue hardship?”

Disability.

The definition of a disability is:

- any physiological or mental impairment, disorder or condition that substantially limits one or more major life activities;

- a history of such an impairment; or,

- being regarded as having an impairment.

The third bullet point is the greatest concern for employers. “Even if someone doesn’t technically have a disability, if you treat them as if they do, you have just provided them coverage under ADA,” explained Seawright.

Major Life Activities.

A major life activity is, well, virtually everything. The first portion of this category relates to one’s major bodily functions, systems or individual organs, including, among others:

- Bladder

- Bowel

- Brain

- Cardiovascular

- Circulatory

- Digestive system

- Genitourinary

- Immune system

- Musculoskeletal

- Neurological

- Reproductive functions

- Respiratory

The second part of this category relates to activities and includes:

- Bending

- Breathing

- Caring for one’s self

- Communication

- Concentrating

- Eating

- Hearing

- Interacting with others

- Learning

- Lifting

- Reaching

- Reading

- Seeing

- Sitting

- Sleeping

- Standing

- Talking

- Thinking

- Walking

- Working

Impairments.

Impairments are mental or physiological disorders or conditions. The regulations identify specific types of impairments that should easily be concluded to be disabilities. Some of these include:

- Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD)

- Bi-Polar Disorder

- Cancer Major

- Depressive Disorder

- Diabetes

- Epilepsy

- Intellectual Disabilities

- Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD)

- Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

An impairment need not be active to be considered a disability. A history of having an impairment also qualifies. “The Act addresses episodic disabilities or those that may go into remission, but still can significantly limit a major life activity when active, such as depression, epilepsy or post-traumatic stress disorder,” said Seawright.

Conditions such as asthma, a bad back, a broken limb and obesity also may be considered “impairments” under ADA. To determine if these types of conditions meet the definition of a disability, employers must evaluate the facts on a case-by-case basis.

“The ADA prohibits employment discrimination against qualified individuals with a disability. The word ‘qualified’ is really important,” said Seawright. A qualified job candidate must meet job-related criteria such as education, experience, training and certification. The law only protects those who meet such criteria qualifying them for a specific job. “If a job candidate is unqualified for the position being sought, there’s no obligation to reasonably accommodate him or her because there is no coverage under ADA,” she said.

Reasonable Accomodations.

A reasonable accommodation is a modification or adjustment to a job, the work environment or the way things are usually done that enables a qualified individual with a disability to enjoy an equal employment opportunity. The EEOC provides several examples: restructuring the job; modifying a work schedule, such as part-time instead of full-time; providing necessary adaptive equipment, such as a phone equipped with volume control for a hearing impaired person; adapting test or training materials, or policies; providing interpreters; reassigning the person to a vacant position; extending leaves of absence beyond what is generally offered; and making facilities accessible.

“This is the short list. Employers must assess each individual and situation to determine what accommodations can be made, and must make an effort to do so,” said Seawright. Reasonable accommodations must be made for qualified applicants and employees with a disability unless the employer can demonstrate that the accommodation poses an undue hardship on the business.

Undue Hardship.

If making accommodations poses a significant difficulty for the business, it may be considered an undue hardship. “An undue hardship is a very high standard to meet,” said Seawright. “Making the accommodation must be significantly difficult or costly to qualify as an undue hardship. Employers shouldn’t count on undue hardship as a loophole to avoid ADA requirements.”

Undue hardships focus on the resources and circumstances of the employer with regard to the cost or difficulty of providing specific accommodations. Financial difficulty is only one aspect of an undue hardship. Others that may be considered as imposing an undue hardship include those that are extensive, substantial, or disruptive, and those that would fundamentally alter the nature or operation of the business.

Employers must assess, on a case-by-case basis, whether a particular accommodation would be reasonable or cause undue hardship, taking into consideration a number of factors including, but not limited to:

- Nature and cost of the accommodation

- Type of operation of the employer

- Location and type of employer facilities

- Overall financial resources of the facility making the accommodation

- Number of employees at the facility

- Effect on expenses and resources of the facility

- Impact of the accommodation on the operation of the facility

Sound Advice.

From a practical standpoint, Seawright offers employers a number of tips to help ensure compliance with the ADA. Don’t ask medical questions of job applicants before an offer of employment. The only time you can ask medical questions is after an offer of employment has been made and before the individual starts working. Questions must be job-related and consistent with all employees in the same job category. Health history questionnaire forms are generally discouraged.

If an employee admits, or you observe, they are unable to do their job due to a medical condition, don’t wait. Start a discussion with the employee about the problem with the goal of resolving it.

If an employee can’t work due to a medical condition? When applicable, initiate a leave of absence as soon as you’re aware of the medical condition, work-related or not, and the need for time off.

“There are business owners who don’t believe in granting leaves of absence unless it’s an FMLA-covered event, and this can be a dangerous position to take. Even if the business is not covered under the FMLA or an employee is not yet eligible for FMLA, in many cases, granting a leave of absence would be considered a reasonable accommodation if the individual is disabled. Such accommodations should be granted unless they create an undue hardship,” explained Seawright. Extending leaves of absence also may be considered a reasonable accommodation. Of course, each case is different.

|

About Jean Seawright Jean Seawright is president of Seawright & Associates, a human resources management-consulting firm located in Winter Park, Fla. Since 1987, she has provided human resource management and compliance advice to employers across the country. For the past 13 years, she has served as NPMA’s human resources consultant to members. She can be contacted at 407/645-2433 or [email protected]. |

If you think an employee with a medical condition poses a direct threat to safety, communicate with physicians to the extent possible. Employers can require, as a qualification standard, that employees not pose a “direct threat” to the health or safety of him- or herself, or others. If you have a reasonable belief that an injured or ill employee may pose such a threat, communicate with the treating physician. Send a letter that describes the physical and mental demands for the job and the basis for your concern. Ask the physician for his or her opinion about the ability of the employee to safely perform the required tasks. Evaluate the response in light of the ADA. “Ask, point blank, ‘Based on your medical judgment, can this person perform these duties safely without posing a risk of health or safety to himself or others?’ said Seawright. “If the information provided by a physician is ambiguous, don’t be afraid to ask for clarification.”

Although an employee may be willing and able to get back to work, it’s not up to him or her to decide when they’re able to return to work after a medical leave of absence. “The worst thing you can do is make a medical judgment yourself or rely on an employee to tell you, ‘I can do this’ or ‘I can’t do that,’” explained Seawright. Turn to the physician; he or she is the expert.

Make decisions on a case-by-case basis. When addressing employee medical issues, “It’s important to make sure all the facts of the situation are being considered,” said Seawright. “Don’t just blindly apply a policy. There’s too much at stake. And don’t delegate this responsibility to someone who doesn’t understand what’s involved.”

ADA regulations are complicated, making compliance equally complicated. As an employer, it’s your responsibility to comply with the regulations. To minimize risk to the extent possible, consult knowledgeable professionals who can guide you through the process. “I didn’t know” won’t justify non-compliance and the ramifications of not knowing can be extremely costly.

“There’s a lot involved. Keep in mind, navigating employee medical issues is both an art and a science,” Seawright said.

The author is a freelance writer based in Milwaukee. Email him at [email protected].

![[HR Matters] Managing Employee Medical Issues - PCT](http://disabilitylaw.news/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/HR-Matters-Managing-Employee-Medical-Issues-PCT.jpg)

Comments are closed.