Missoula veteran, well being care advocates problem $1B reduce to human companies funds ~ Missoula Present

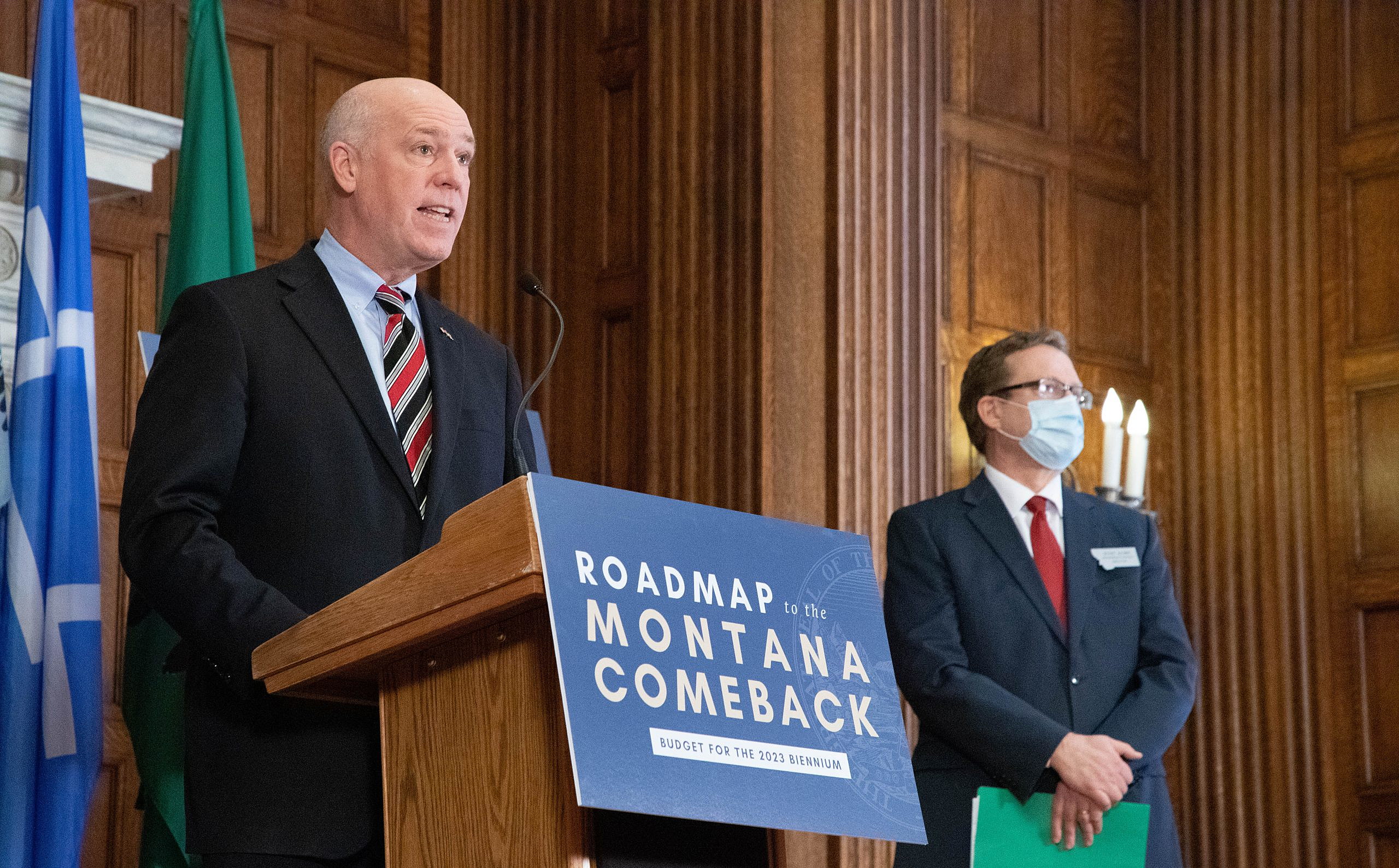

Republican Governor Greg Gianforte unveiled his budget proposal in a press conference Thursday at the Montana Capitol in Helena. The proposal promises to decrease government spending by $ 100 million over the next two years. (Austin Amestoy / UM Legislative News Service)

Republican Governor Greg Gianforte unveiled his budget proposal in a press conference Thursday at the Montana Capitol in Helena. The proposal promises to decrease government spending by $ 100 million over the next two years. (Austin Amestoy / UM Legislative News Service)

Travis Hoffmann asked lawmakers on Friday how often to shower.

The Missoula man, a U.S. Army veteran and person with disabilities, said he already needed help showering and was limited to three times a week due to limited resources. Further cuts in what he already believes to be the troubled health and personal services sectors would mean cutting back on very basic services like showering.

“I assume you can all shower whenever you want, but I can’t,” he said.

On Friday, when the Health and Human Services Shared Funds Subcommittee was working on the budget bill, the Republican-dominated group voted 5-2 to use actual 2019 spending as the basis for preparing the biennial 2021-2022 budget for the year to use Department of Health and Human Services. This department alone accounts for more than 40 percent of the state budget.

However, using the 2019 budget as a starting point would mean nearly $ 1 billion less for the agency than suggested by Greg Gianforte, governor of Montana. Democrats and members of the public argued that such a cut, if successful, would cause an implosion in services from memory maintenance to addict treatment.

Brooke Stroyke, a spokeswoman for Gianforte, said the governor intended to work with the legislature but plans to keep spending while not cutting back on essential services.

Republicans pointed out that the numbers they proposed were merely a starting point for starting discussions, and no one during the committee’s testimony believed that the 2019 numbers would be the budget that will be adopted in 2021.

The proposed rollbacks, which form a basis for the new budget, are spread across the 16 different departments of the DPPHS, sometimes referred to as “programs”, with each of these departments managing different services. In a press release, Democrats noted that if the proposal went into effect, it would cut $ 96 million on Disability Services, $ 96 million on Senior Long Term Care and $ 34 million on Addiction – and mental illness.

“This is just a vote on where to start building a budget,” said Senator Keith Regier, subcommittee chair, R-Kalispell. “We’re not using any money today.”

Republicans argued that 2019 was the last actual numbers to close, so it was the best choice for creating a “real-world” budget. Democrats and members of the public argued that these numbers are not an accurate representation as there have been many cuts to pass legislation during this budget cycle and that many health services and agencies have still not fully recovered from the cuts in 2017.

“You can now build up the budget again. However, in my view, this is a straightforward cut and approach that other subcommittees do not intend, ”said Heather O’Loughlin, co-director of the Montana Policy and Budget Center.

O’Loughlin said the actual numbers are available from more recent ones.

“We’re going back to three years ago, which may or may not make sense,” she said. “But we will spend a fair amount of time justifying expenses without going into what is needed in our church now and what is emerging.

“You don’t usually start three years ago.”

State Senator Mary Caferro, D-Helena (Legislative Intelligence Service Freddy Monares / UM)

State Senator Mary Caferro, D-Helena (Legislative Intelligence Service Freddy Monares / UM)

Rep. Mary Caferro, D-Helena, said she would like to see how many jobs would be affected by these proposed cuts.

“I’ve seen this rodeo before. My opposition is not to transparency, but I have cited programs – many programs – where we had to cut services or even cut staff, ”said Caferro. “I have no problem editing programs and eliminating those that don’t work.

“But we cannot go back until 2019. I cannot vote hypothetically with so much at stake. This is a cut – and I know you don’t see it that way, but it means a loss of jobs, cuts for thousands of people, including children, who are being abused or neglected, “she added. “There’s nothing hypothetical about that.”

Regier replied that the proposal, against which Senator Mary McNally, D-Billings and Caferro ultimately voted, served its intended purpose in stimulating discussion and[shining] a light on where all the money goes. “

Health care providers and attorneys have appeared in person and via video to raise concerns. Lobbyist Joel Peden of the Montana Association of Centers for Independent Living, which represents three nonprofits, including those in Helena and Billings, said even modest cuts could have an oversized impact.

“In 2020 we received a small increase for services,” said Peden. “That’s the difference between us and not offering some services.”

Former lawmaker Pat Noonan, who represented the Behavioral Health Alliance, which includes 30 communities in Montana, put it worse.

“Community Behavioral Health Providers are afraid. They’re scared of what’s going to happen, and they’re even more scared today, ”said Noonan.

After cuts to DPHHS in 2016, Noonan said many small vendors in rural Montana have closed their doors. Now, he said, there are few mental health service providers east of Billings, the state’s largest city.

“You need a substantial raise, but that may not be possible,” Noonan said. “But if there are cuts, we won’t all survive.”

O’Loughlin also said the department isn’t as flexible as it might seem at first glance.

“The reality of health and personal services is that there is only so much you can cut,” said O’Loughlin. “There are services that the state is obliged to provide.”

Often times, lawmakers make cuts on essential services by continuing the services, but at a lower reimbursement rate. Paying providers less to do the same job can force them to make one of two dangerous decisions – either close down or refuse to accept government payments.

“The reality is that this means a loss of service and providers,” said O’Loughlin.

The other option is to cut back on what the state sees as “optional services,” O’Loughlin said.

“That’s what they’re called, but in my eyes and in the minds of many, they’re not optional,” said O’Loughlin.

Often times, optional services are the most efficient and help save money in other areas as well, she said. For example, home care services are often viewed as optional, but they run more efficiently than institutional accommodation.

Mary Windecker

Mary Windecker

Mary Windecker of the Behavioral Alliance for Montana said that Montana stands out for its mental health treatment, and not for the right reason.

“We have fallen from No. 1 in the country to No. 3 in suicides,” she said. “But that’s because these other states did such a terrible job, not because we necessarily did better.”

Montana is already the leader for most children in protective services per capita, and the number of children in foster care has doubled in less than a decade.

Windecker said that Montana Indians die a generation earlier than their non-native counterparts. She told lawmakers that a week of imprisonment often costs more than a year of community service.

“You can either pay now or pay later,” she said.

Many of those who testified said that COVID had increased the burden on social services, be it assistance with accommodation or mental health.

Diane Reidelbach, who leads Job Connection in Billings, saw the number of people needing her organization’s service increase by 60 percent.

“We’re holding on,” she told the legislature. “But by a thread.”

The committee will meet again Tuesday to hear a biennial Medicaid report.

This story originally appeared online at DailyMontanan.com and is republished here with permission.

Editor’s Note: This story has been edited to correct the spelling of Heather O’Loughlin.

Comments are closed.