The Pandemic Made It Tougher to Spot College students With Disabilities. Now Faculties Should Catch Up

Kanisha Aikin had suspected her son, Carter, might have dyslexia, but it wasn’t until his Katy, Texas, school closed in March 2020 that she was certain.

Carter, then in 1st grade, quickly switched to remote learning alongside millions of students around the country as leaders struggled to contain the COVID-19 pandemic. That gave Aikin a rare chance to watch her son’s day-to-day learning experience up close.

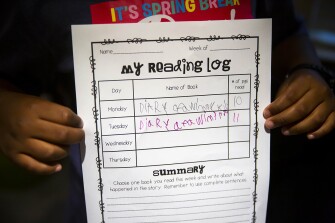

As his virtual class did reading exercises, Carter struggled to blend sounds together. Even after seeming to master a word on one page of a book, he failed to recognize the same word a few pages later. Sometimes his frustration would lead to misbehavior or a lack of focus. And his reading skills were noticeably different from his classmates’ and even his younger sisters’.

Regardless of the world shutting down, time was still passing and he was still going to have to go to 2nd grade next year.

Kanisha Aikin, parent of a child with dyslexia

“I was panicking,” Aikin said. “I thought, ‘If we don’t do something quick, he’s going to be in trouble.’ Regardless of the world shutting down, time was still passing, and he was still going to have to go to 2nd grade next year.”

Nationwide, 7.3 million students, around 14 percent of all public school students, receive services under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, the nation’s primary special education law. Policymakers have sounded alarms about meeting those students’ needs during the pandemic, and some fear there are children who need those services who haven’t been identified at all.

Parents and teachers are often the first to recognize the signs of disabilities in students. That’s especially true of students with learning disabilities, whose needs may not be as immediately obvious as those of other students who need special education services. And, during the pandemic, both parents and teachers have faced significant interruptions that have made recognizing those needs more difficult, educators told Education Week.

Like Aikin, some families flagged concerns as they supervised their children’s participation in online lessons. But many other parents—including those who couldn’t afford work interruptions—didn’t have the option of staying home to monitor their children’s remote learning or might not have recognized any subtle issues as they emerged.

For teachers, extended periods of remote learning or class time interrupted by frequent quarantines robbed them of the small ordinary encounters that can help them gauge students’ progress: how quickly children turn pages, how they engage with peers, how they respond to frustrations with reading and math exercises, even the appearance of their handwriting, which may have been replaced by typing into an online program.

Those dynamics combine with other challenges to form a perfect storm for schools as they seek to return to normal: They must work to separate which students need assessments for learning disabilities and which children’s academic struggles can be attributed to the ordinary fidgeting and grimacing that comes with learning in front of a computer.

Educators must work to recognize concerns that may have gone unidentified and to prioritize which newfound parental concerns are the most urgent. Many will do so with less data from classroom assessments and statewide exams than they would have in a typical year. And they will tackle those needs as they also strain to accommodate heightened social and emotional stress for all students after an unprecedented set of school years.

“It’s going to be really difficult to assess where students are and to determine whether what we are seeing is the result of a disability or a new baseline for everyone,” said Meghan Whittaker, the director of policy and advocacy for the National Center for Learning Disabilities.

Looking for warning signs of disabilities

With a family history of dyslexia, Aikin said her “radar was turned on very high” to warning signs for her children. As she studied up on the special education process, she enrolled Carter in a small private program focused on reading instruction for the last school year. After recently getting a formal evaluation and diagnosis from her school district of dyslexia and dysgraphia, a disability related to handwriting, she’s weighing her options for the 2021-22 school year.

But there may be many children showing similar warning signs of disabilities that have gone undetected, said Winnie Williams-Hall, an 8th grade special education teacher in Chicago.

The early signals of disabilities can be very difficult for parents, and even teachers, to recognize, she said. And remote learning made that even more difficult for educators.

“During in-person learning, you are face-to-face with a student, and you can gauge facial expressions, when you need to slow down,” Williams-Hall said. “But that’s difficult to do during virtual learning and the student doesn’t even have the camera on.”

Similarly, while a student with a behavioral disorder or emotional disturbance may physically disengage or seem defiant in an in-person classroom, that same student may mute their microphone and ignore their computer in remote learning, and it can be difficult for educators to determine why they are absent from class discussions, Williams-Hall said.

During in-person learning, you are face-to-face with a student, and you can gauge facial expressions, when you need to slow down. But that’s difficult to do during virtual learning and the student doesn’t even have the camera on.

Winnie Williams-Hall, a special education teacher in Chicago

Even for teachers familiar with learning disabilities, the sound quality and limitations of computer programs may have made it difficult to recognize them last year, said Teresa Ranieri, a teacher and literacy coach at a New York City elementary school.

During online reading exercises, it could be difficult to hear if a student was able to blend letter sounds together to form words, to deconstruct words into individual phonetic sounds, and to rhyme, she said.

“There’s a delay, there may be poor internet connection, and when all of the children say it at the same time, it’s very hard to hear them,” Ranieri said.

With a focus on science-based reading instruction, Ranieri’s school does universal assessments to gauge students’ reading skills and to determine who may need more-targeted evaluation. But those assessments were written to be administered in person, she said, and it’s difficult to measure how much online administration affected the reliability of their results.

With parents’ permission, Ranieri donned gloves and a mask and went to twin students’ home to evaluate them in person last year.

“I was able to identify strengths and needs so much more because I did it in person,” she said. “In my mind I’m thinking, ‘How can I go to everyone’s home to do this?’ ”

Online learning presents challenges

There’s no federal year-over-year data on special education evaluations, and states that tabulate such information do not yet have information on the 2020-21 school year. But signs point to a decline. In Indiana, for example, schools completed about 25,000 special education evaluations during the 2019-20 school year, which included the first few months of the pandemic. That was a 16 percent drop from the previous year, state officials told radio station WFYI. They cited school closures and drops in public school enrollment.

During the second half of the 2020-21 school year, more schools around the country that had operated remotely began to offer in-person or hybrid instruction. But even then, many families opted to keep their children at home.

For Williams-Hall, a return to the physical school building meant two students in the classroom and the rest of them on screens, an experience shared by many of her fellow teachers.

In a nationwide poll of parents conducted by NPR/Ipsos in March, 48 percent of respondents agreed with the statement “I am worried my child will be behind when the pandemic is over.”

School psychologists—who evaluate children for disabilities and help plan interventions and individualized education plans—anticipate an uptick in concern about issues like time management, student engagement, and social and emotional well-being.

Some parents and educators may also be unsure if students’ struggles can be traced back to a disability that requires targeted interventions, said Kelly Vaillancourt Strobach, the director of policy and advocacy for the National Association of School Psychologists. And, while schools want to identify the students in most urgent need of support, they will also want to avoid historical concerns about overidentifying students—particularly students of color—for special education programs.

“We are worried about districts and schools using special education as a remedy for what happened in the past year,” Vaillancourt Strobach said. “You want to make sure you are accurately identifying students.”

Further complicating the process: Federal special education regulations call on schools to rule out a “lack of appropriate instruction” before diagnosing students with specific learning disabilities, which include processing issues that affect a student’s ability to listen, think, speak, read, write, spell, or do mathematical calculations. Interruptions posed by the pandemic may make it difficult to rule that out.

The NASP and other organizations that advocate for students with disabilities have recommended that schools use federal COVID-19 relief aid provided through the American Rescue Plan to reengage all students through multitiered systems of support, through which educators use a leveled approach to provide increasingly intense help to students with academic or behavioral difficulties.

In such programs—like response to intervention and positive behavior interventions and support, or PBIS—Tier 1 includes all students. Tier 2 provides more moderate supports for students who need it, often through small group instruction, and Tier 3 provides more intense, one-on-one intervention for students with the highest degree of needs.

“In a typical year you will probably see 20 percent of your students need a little bit more” support Vaillancourt Strobach said. “What we are expecting this year is maybe 80 percent will need a little bit more.”

If students respond well to the lower level of support, that means they may have just needed some help reenaging after an atypical school year, psychologists said. But if they struggle even as they advance up the tiers, they may need to be evaluated for special education services.

We really need to understand why they are so far behind. We have to be careful and intentional in that process.

Meghan Whittaker, director of policy and advocacy at the National Center for Learning Disabilities

“We really need to understand why they are so far behind,” said Whittaker, of the National Center for Learning Disabilities. “We have to just be careful and intentional in that process.”

But the multiple-tier approach has its critics, including advocates for students with disabilities who say schools don’t always have the resources to implement it well.

Whittaker said she hopes that schools will work quickly to invest in improving their systems.

“We have not implemented strong [multitiered systems of support] the way we need to,” she said. “Now we are putting such a magnifying glass on this issue. I’m really hoping that now is the time we really do something about this.”

But to anxious families who have seen signs of possible disabilities in their children, anything short of an immediate, individualized response could seem like stalling, some parents told Education Week.

That was the case for Lauren, a Massachusetts mother who did not wish to use her last name to protect her children’s privacy. During the pandemic, she noticed her twin sons, who just completed kindergarten, struggled with understanding phonics instruction.

“Everyone said, ‘Don’t worry about it. All kids are struggling. All kids are having problems,’” Lauren said.

But, after seeing one of her sons confuse letter sounds and get frustrated with rhyming exercises, Lauren insisted on an in-person evaluation. Her school district complied, and a psychologist sat with her son outside the administration building to assess him, using the outdoor air as a virus precaution.

After seeing him in person, the evaluator quickly agreed Lauren’s son needed targeted supports, and said his descriptions of his own experiences with reading sounded like textbook dyslexia, Lauren said.

After some discussion with the school, Lauren opted not to evaluate her other son right away. Instead, she will watch his progress as he participates in the same small groups and academic enrichment programs his school plans to offer all of its students as it focuses on pandemic recovery.

“I’m still a little wary that another issue might pop up,” she said.

A confusing process for parents

Parents who had concerns about their children’s learning told Education Week that the process of pursuing evaluations for special education, supporting their children’s academic work, and working with schools to create individualized education plans was overwhelming and confusing, even with supportive school leaders on their side.

Liana Durkin, an Alpharetta, Ga., single mother with a demanding work-from-home job, said it began to feel like “a full-time job” to help her 6th-grade daughter, Rylee, keep up with assignments, pay attention during six-hour days of online classes, and process concepts she clearly struggled to grasp.

After seeking her own diagnosis by an outside psychologist, Durkin requested a formal evaluation from Rylee’s school that later confirmed she needed support for ADHD. The process was confusing, and Durkin relied on advice from other parents and Facebook groups, where she heard stories about issues like delayed evaluations, confusing meetings with administrators, and a lack of support.

“I kept thinking about, yeah, I can’t even imagine the parents who have to go into work every day,” Durkin said.

In many cities, concerns about a backlog of special education evaluations predate COVID-19. But, even in the earliest days of school closures, there were signs the pandemic had exacerbated the problem.

As Congress deliberated its first relief bill, the CARES Act, school district administrators pushed for waivers from some parts of IDEA, including timelines in the federal special education law that require evaluations to be completed within 60 days of a formal request. They cited an inability to do things like conduct assessments or provide supportive therapies for students learning in remote environments.

Asked by Congress to evaluate the need for IDEA waivers, then-U.S. Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos said the law’s requirements should largely remain in place, even during the national emergency.

“With ingenuity, innovation, and grit, I know this nation’s educators and schools can continue to faithfully educate every one of its students,” she wrote in April 2020.

Concerns about evaluation backlogs

But there are some signs schools failed to fulfill those mandates.

In March, for example, five Texas families sued the Austin Independent School District, claiming the school system had failed to respond to stalled requests for student evaluations and reevaluations. The district has since worked to address the backlog.

In August 2020, the state of Massachusetts intervened after a disability rights organization complained that the Nashoba Valley Regional School District had suspended all in-person evaluations, leaving some children in limbo.

Beyond those unmet requests, advocates are concerned about children who have fallen through the cracks because theteachers and educators who might normally notice their struggles failed to see them.

Aikin, the Texas mom, sees the progress her son has made after she identified his dyslexia, but she’s mindful that many other children’s needs may have gone unnoticed.

“So many children are missed and overlooked,” she said.

As she weighs whether to send Carter back to public school in the coming school year, Aikin has seen signs of progress.

Her son who once ran away from reading assignments now asks to go to the library and bring books with him in the car. Recently, the family was passing through a restaurant drive-thru when Aikin heard Carter pipe up from the back seat. He was trying to read a sign out loud without any prompting.

“I almost hit the car in front of me,” she said. “The fact that he was initiating, trying to read, was step one.”

Comments are closed.