Syrian refugees registering with UNHCR in Jordan using IrisGuard technology. (Photo courtesy of IrisGuard)

Since Brazil and Mexico introduced the first conditional cash transfer programs in the 1990s, governments, international organizations, and humanitarian organizations have implemented this economic development policy tool worldwide.

Highly varied in conception, design, implementation, and evaluation, cash transfer programs – also known as disbursement programs – seek to alleviate poverty, but they often struggle to meaningfully impact hard-to-reach populations who are most in need. How do we deliver cash transfer and digital disbursement programs effectively to the hardest to reach? How do we extend benefits to urban refugees, those who are geographically remote, those who lack a legal identity or live in extreme poverty?

At the Reach Alliance, we aim to understand how and why social programs are effectively reaching (or failing to reach) these populations and communicate actionable insights to policy makers and practitioners. After investigating four cash transfer programs across Brazil, Ethiopia, Jordan, and Palestine, we found five features critical to success: comprehensive data, flexible targeting, caution around conditionalities, technology use, and partnerships.

1. Comprehensive Data

Households in need are sometimes excluded from receiving cash transfers when implementers neglect to account for a variety of socioeconomic factors. For example, the Palestine National Cash Transfer Program (PNCTP) uses a proxy means test formula that in addition to approximating household income, classifies woman-led households and households including a person with a disability, an illness, or elderly member as “vulnerable.” This process captures households that may be excluded by income assessment alone. Additionally, cash transfer programs can adapt standard assessment criteria to account for regional socioeconomic vulnerabilities. For example, Ethiopia’s Productive Safety Net Programme (PSNP) uses a Programme Implementation Manual with nine guiding principles that can be adapted locally to address specific household needs such as administering food instead of cash transfers when it is more helpful to combat food insecurity. Notably, the PNCTP’s targeting mechanism falls short in accounting for unemployment and structural market problems resulting from the blockade of Gaza. Overly simplified data or not accounting for contextual variables obscure people’s true needs.

2. Flexible Targeting

Programs without flexible targeting methods can overlook those most in need. By making adaptations for cultural differences and considering the role of community members in identifying recipients and delivering and monitoring transfers, limited resources are allocated to recipients more effectively. For example, cultural norms among nomadic clans located in the lowland regions of Ethiopia dictate that wealthier clan leaders collect transfers and redistribute support to families. The PSNP relies entirely on community-level decision-making to select recipients, allowing for low-cost, high-accuracy targeting, which makes it the most successfully targeted state-led social safety net in Africa.

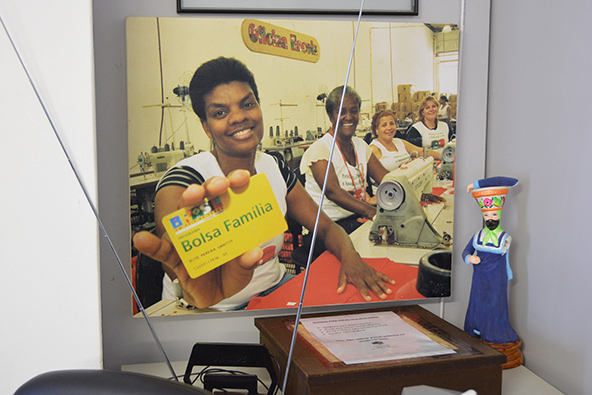

A poster in a government office in Brazil depicts Rute Pereira Santos, a beneficiary of the Bolsa Família Program, holding up her electronic benefits card used to withdraw cash transfers. (Photo courtesy of the Reach Alliance)

Leveraging community knowledge to target recipients also mitigates data gaps and complements program databases. In Brazil, municipalities, community centers, and community health workers are the “capillaries” of the country’s social safety net and are essential implementation and referral partners for the Bolsa Família Program (BFP). The biggest example of this are the community health agents of Brazil’s Family Health Programs who are responsible for going door-to-door within their assigned community to get to know the residents, refer them for eligible supports and services, and follow up on BFP conditionalities. To this end, potential beneficiaries are identified through an active search, rather than waiting for beneficiaries to independently seek out and apply for the program. Community-based targeting gives the program the necessary flexibility to address specific community needs, better monitor conditionalities, and reduce errors.

3. Caution Around Conditionalities

Policy makers often think of conditionalities as a way to address poverty both immediately and in the long term by requiring recipients to engage in specific behaviors (e.g., attending school, receiving mandatory vaccinations) that are assumed to alleviate poverty. Despite these benefits, conditionalities are not a one-size-fits-all solution. Programs responding to ongoing political and humanitarian crises, such as the PNCTP or UNHCR Jordan’s biometric cash-assistance program, are unconditional and focused on establishing a safety net to allow recipients to cope financially, rather than incentivizing behavior change. Introducing conditions in contexts with high poverty rates and limited public services could harm beneficiaries. The high risk for noncompliance, and the burden and cost of complying with conditions to maintain the transfers, could further limit people’s already constrained resources. However, where public resources are available, such as with the BFP, the implementation of conditionalities can play a useful role in breaking intergenerational cycles of poverty in addition to addressing short-term needs.

Linking conditionalities to existing public services can reduce the set-up, maintenance, and monitoring costs of cash transfer programs. For example, the reliance of the BFP’s conditionalities on Brazil’s Unified Health System facilitates the monitoring and reporting of compliance to other government bodies. Similarly, linking conditionalities to public services places the burden of reporting on public services, rather than on beneficiaries. Before using conditionalities to encourage increased public service usage, policy makers should assess the availability, accessibility, and quality of these services and explore whether demand for services could be increased through investments on the supply side. For example, supply-side factors that could lead to low school attendance include transportation fees, school fees, or the cost of school supplies. Addressing these barriers may in some cases be enough to increase enrollment.

4. Technology Use

Our investigation found that cash transfer programs lacking data consolidation, coordination, and security measures undermine program delivery and can lead to duplication of services and increased administrative costs. Using tech-enabled databases, when possible, consolidates information and implements strong, coordinated data security policies that protect program recipients. Cadastro Único, Brazil’s single social registry, is the BFP’s backbone. Well-maintained data on more than 27 million low-income households provide a detailed “map” of poverty in Brazil. This national database allows program administrators to determine and monitor eligibility for the BFP in addition to 30 other complementary government-sponsored social assistance programs, all while reducing possible duplication of benefits and reducing administrative costs.

UNHCR Jordan uses EyeCloud, an integrated server, to protect data security. Cash transfer recipients are recognized by encrypted iris scans when using Cairo Amman Bank ATMs. Once they’re verified in the UNHCR EyeCloud server and a match is found, beneficiaries receive cash from the ATM. Sensitive biometric data are protected and the need for time-intensive and expensive recipient authentication is eliminated. In addition to producing cost savings, this technology enables frontline workers to spend more time on qualitative engagement with recipients.

5. Partnerships

Solving for the nuanced problem of delivery—how to get money transfers and other social services to the hardest-to-reach populations—requires stakeholders from the public, private, and third sectors to move beyond traditional partnership models. Cash transfer programs are often inefficient when it comes to delivery. To address this problem, involve private sector companies with assets and expertise, especially related to technology and infrastructure. For example, IrisGuard, an international technology company based in Jordan, supplies the Cairo Amman Bank with its iris-scanning technology, mentioned above, which helps UNHCR Jordan save considerable financial resources that would otherwise be spent on in-person verification checks or lost and stolen bank cards. This partnership resulted in approximately $0.95 of every dollar reaching Syrian refugee families, increased from roughly $0.75 of every dollar reaching recipient families in traditional transfer programs.

Another example of innovative partnership is the Common Cash Facility, a payment structure negotiated between UNHCR Jordan and the Cairo Amman Bank for humanitarian organizations providing cash assistance in Jordan. The structure takes advantage of economies of scale and reduces transfer fees on financial assistance for member organizations. As the amount of money passing through the Cairo Amman Bank for various cash transfer programs increases, transfer fees are reduced (from a maximum transfer fee of 2.25 percent to a minimum transfer fee of 1.45 percent of total transfer value).

Without international donors to support consensus-building on key priorities, program implementation can be fragmented. The PNCTP, a merger of separate European Union and World Bank cash transfer programs, fostered connections between ministries, nongovernmental organizations, and UN agencies to catalyze their delivering a package of social assistance including health insurance, tuition waivers, as well as cash. Leveraging host community connections with civil society organizations helps to bridge state-led or other programs with the wants and needs of target populations. In Ethiopia’s PSNP, collaboration with international organizations and global nonprofits both ensures linkages with other social service programs and expands program reach. Organizations like World Vision and CARE International act as implementation partners within communities and provide capacity-building programs, like financial and digital literacy training, to recipients to improve the effectiveness of food and cash transfers.

Finally, program sustainability is at the greatest risk without government buy-in. Facilitating government involvement at multiple levels is important to support program continuity and longevity. In the case of BFP, the coordinated use of comprehensive census data allows government officials at both the federal and municipal levels to create poverty maps of micro-areas to improve targeting. The census data has also allowed program administrators to identify barriers that might prevent potential beneficiaries from enrolling in the BFP or from accessing the funds transferred to their electronic benefits card (e.g., living in a community without a Family Health Program or living somewhere without access to bank machines). This coordination between federal and municipal governments in Brazil has allowed for creative solutions such as the design of two ATM boats operated by the state-owned bank, Caixa Econômica Federal, which allows the riverside populations in the Amazon to withdraw their BFP cash transfers.

Improving Effectiveness

To maximize finite programmatic resources, cash transfer programs need accurate data to target effectively and determine conditionalities. They also have to figure out what kinds of technology investments to make and what partnership models will best serve their needs. Cash transfer programs are an important poverty alleviation tool that have been proven to increase purchasing power for low-income households and reduce poverty indicators in more than 60 countries worldwide over the last two decades. However, they also have the potential to be incredibly costly to implement, monitor, and operate. Improving their effectiveness is essential to ensuring their reach, impact, and sustainability. These actionable insights are applicable beyond the delivery of digital and cash transfers to the hardest to reach and can be extended to the implementation of social service programs, such as education and health care, to last-mile populations. Extending cash transfer and other public service benefits to the most vulnerable will reduce poverty and also foster greater economic autonomy and self-sufficiency in communities.

Read more stories by Marin MacLeod, Sydney Piggott, Joudy Sarraj & Nicoli Dos Santos Stiller.