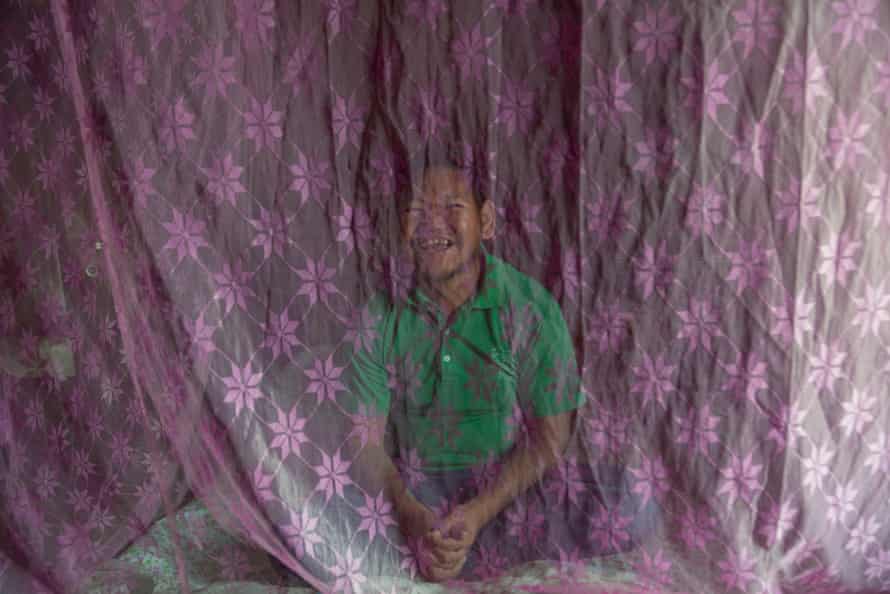

W.When he’s not working on the farm or making things out of jute, Gobinda Majumdar likes to go to a tea stand near his home in Assam to buy sweets for his nieces. He explains all of this with tactile gestures, the only means of communication for the 37-year-old, who can neither speak nor hear nor see.

Born deaf, Majumdar went blind at the age of two after contracting rubella. Life has its challenges, but he hopes to find a wife. “My younger brother is married, so why not me?” He told the photographer Vicky Roy, who visited him in the Kamrup district as part of a project to tell stories of people with disabilities in rural India.

“My goal is to highlight ordinary people with disabilities so that their relatable stories resonate with others like you and create awareness of disability among the general public,” says Roy. “My clear goals are: focus on the person, not the disability; Do not show them as objects of compassion, but as ordinary people pursuing their simple dreams; and make sure that there is an equal mix of male and female subjects. “

Gobinda Majumdar was born deaf and went blind at the age of two. He makes things from jute, bamboo and coconut leaves that he can sell, and his late father taught him how to look after the cattle and run the small farm he lives on with his family

Roy has been traveling around the country for six months – if Covid allows this – taking photos of people with the 21 officially recognized disabilities in India. The Everyone is Good at Something (EGS) project publishes a steady stream of stories to combat the widespread stigma and tabooing. “Hopefully these images will open the discussion about disability and maybe even influence politics,” he says.

“Real change takes time, and we will continue to do so for so long,” said VR Ferose, founder of the India Inclusion Foundation, which co-founded EGS with Roy with the goal of publishing 15,000 stories from every state in the country.

“The law in India is very advanced in protecting the rights of people with disabilities. The problem is, most people don’t know about it, ”says Ferose, a California engineer who started working on disability rights after his son was born with autism 12 years ago.

“We know that people in India don’t talk about disability because there is a feeling of taboo. One reason could be the idea of ”karma,” where people think that someone has a disability because they did something bad in the past, “he says. “We asked ourselves: how can we change this narrative and we decided to do a kind of Humans of New York [a photoblog of street portraits and interviews], but with people with disabilities across India. “

“Disability is possible,” says Tiffany Brar, 30, who runs a training center for the blind. Nincy Mariam Mondly was training to be a paramedic when her spinal cord was injured in a fall. Tariq Ahmad Mir, an award-winning embroiderer, was born with muscular dystrophy. Sohkhotinlen Haokip, 31, has Down syndrome and enjoys being with people

Amer Hussain Lone, who lost both arms at the age of eight, is the captain of the para-cricket team of Jammu and Kashmir

The India census shows that around 2% of the population are disabled, compared with a global average of nearly 15%, suggesting that many people in their families do not talk about disabilities, Ferose says.

Acid attack victims were added to the list of disabled people in 2015 and Roy went to Agra, Uttar Pradesh to meet five women who are helping run the Sheroes Hangout, a cafe and community for acid attack survivors.

Now 27, Roopa was 14 when her stepmother poured acid on her face. Today she takes care of the accounts and designs for the boutique at Sheroes.

The women who run the Sheroes Hangout cafe in Agra. Rukaiya Khathun, front right, was 14 years old when she was attacked with acid. She says: “I used to wear a burqa, but now I feel good in jeans and a T-shirt”

Roy says he’s deliberately looking for stories that have received little attention, but the project also includes some leading activists.

After his leg was amputated after a bombing in the Kargil War, Maj Devender Pal Singh of Chandigarh started running half marathons. Known as India’s “First Blade Runner,” he founded Never Say Die, interviewing former soldiers who have faced similar challenges in life and encouraging other amputees to run.

In Akuluto, Nagaland, Ashe Kiba recalls the cruelty of neighbors who believed she was “cursed” for being born with fewer and shorter fingers. She hid her hands and skipped years of school for ridicule. Eventually, however, she graduated with a degree in English literature and began speaking for the Nagaland State Disability Forum (NSDF), of which she is now the general secretary.

Growing up, Ashe Kiba was mocked by others who believed she was cursed because her hands were different. She wanted to drop out of school, but her mother encouraged her to keep going. She graduated with a degree in English Literature and decided to become a voice for others like her. Today she is Secretary General of the Nagaland State Disability Forum. Her message to all people with disabilities is: “Be strong and fearless. We have to accept our uniqueness. Let’s not hide ‘

Each story consists of five pictures, with the subjects photographed at home – in their own “kingdom,” says Roy – with their families.

“Society ignores people with disabilities or treats them as inferior people. It doesn’t give them a chance to reveal their thought-provoking views, diverse skills, and even humor, ”says Roy, who will eventually recruit other volunteers for the project.

From left the friends Simi Kalita, Sisila Das and Runu Medhi, who live in Guwahati, Assam. Sisila developed polio when she was two years old. Runu was a premature baby whose twin died in childbirth and suffered from cerebral palsy. Simi, Runu’s cousin, also has cerebral palsy

“When we get home to people, they are very hospitable,” says Roy. “They say they are happy to see us because they are finally getting respect.”